Exploring the South Pacific

49 Days on a Cargo Ship

|

This is the author's first sea trip on a freighter. The journey begins in Panama and goes west to Tahiti, Fiji, New Caledonia, Australia and New Zealand, and then back to Panama.

Travelogue & photos:

Sandra Shaw Homer

Panama Canal, Panama

One of the most extraordinary engineering works

|

When I boarded, it was dense, Panamanian hot. I went to bed early, knowing we would get under way during the night, and in the pre-dawn - after a night of thudding and ship-shuddering each time we took on another container - I awoke to silence. We were moving.

I went out on deck to feel the night breeze on my cheek and watch as we glided silently past the lights of Port Cristobal, the sky just paling to pink on the horizon. I was headed for the north end of the Panama Canal on the first of a 49-day freighter voyage around the South Pacific.

|

Two tugs scuttled alongside to guide us into the first lock, and then scooted away just in time to avoid being squashed. Then hefty little locomotives took over - mulas that keep the ships from banging into the sides or charging the gates, maintaining ship's lines at just the right tension throughout the passage from one chamber to the next.

It was an all-day cruise through one of the most extraordinary engineering works ever built.

|

After passing the first locks, we slid along the jungly shores of Gatún Lake and then entered the serpentine Culebra Cut, a narrow channel between steep cliffs terraced to control erosion. But the walls are still eroding 100 years later, keeping dredgers alongside the channel full-time.

My overwhelming impression of the Canal was the battle between human labor and a formidable environment - how did they ever dig through all these mountains and jungles?

|

As day closed down, we left the glittering Oz-like towers of Panama City behind, along with a tropical downpour drenching the coast under a leaden curtain of cloud.

|

We were finally at speed toward the western sun, the invisible bow roiling up salt-milk vortexes along the hull in the inky water. There were a couple of whales far off to starboard, a mother and calf, breaking and slapping their tails. What magic! We were leaving the land behind for the next ten days until Tahiti.

|

There are only three passengers on board, Cristi, Lila and I, all from different countries and within a year or two of sixty, traveling alone on our first freighter voyage, without knowing each other beforehand. The Captain calls us 'the ladies.'

|

The Chief Engineer asked why I was taking this voyage. 'It's not about the destinations,' I said and turned to look out the window at the three-meter waves rolling inexorably by. The sea had always held for me a fascination touched with fear.

|

I had spent plenty of time on small boats when I was young, and I knew the dangers as well as the peace that an endless horizon brings. I turned back to the Chief. 'I just wanted to be on a ship out in the middle of the ocean,' I said.

Manzanillo, Panama

The difference between pitching and rolling

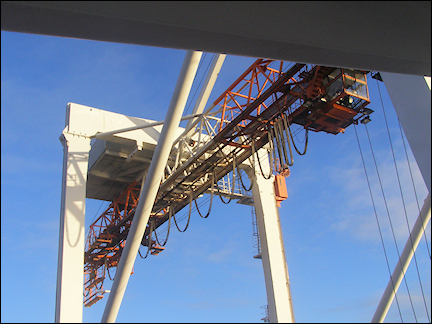

It doesn't take long aboard a cargo ship to realize that it's all about moving things - not people - from one part of the planet to another, and the scale is impressive. In a port the size of Manzanillo, Panama, huge gantries slide up and down the docks on tracks, lean out over the ships and then, with giant jaw-like cranes, swoop containers off the backs of trucks and up, up and over to their exact location on board.

|

A crane operator up under the gantry zips back and forth in his little glass cage working the dozens of cables needed to control all this. And it goes on night and day. Time is money.

On board orientation: safety first, safety first... and don't throw anything into the sea. The engine room was an inferno of noise, even with ear-protectors, but the workings in the belly of the ship were as fascinating as they were Dante-esque.

There is no level place to put anything down in the bathroom. My shins have discovered the corner of every piece of furniture in the room. And the Captain likes a chilly ship: the temperature in my cabin has yet to exceed 73 F. We're in the tropics and I'm wearing long sleeves!

|

I asked the Captain to remind me of the difference between pitching and rolling. His explanation: if the waves are coming on the bow, the ship will pitch, diving nose-first into the trough of the wave before climbing back up. If the waves are on the beam (sideways), the ship will roll, tilting side to side.

If the waves are on the stern quarter - not directly on the stern but coming from slightly port or starboard, as now - the ship is yawing, which is a combination of pitching and rolling. If you can imagine the bulk of a cargo ship doing a three-quarters wiggle between a roll and pitch, you've got it.

The Captain explains that these stern-quarter waves are radiating out from a huge storm off Argentina, 3,000 miles away, and I have to wonder how big they were to start with!

The sunlight streaming through the patchy clouds turns the surface of the sea to beaten silver.

|

The barbecue party was held aft on the poop deck (the aft-most end of the main working deck). The vast space was roofed with the undersides of containers, the reefers dripping condensation on the long table. The poor lighting made everything appear a uniform black against the nighttime sea, only the pipes and fittings stark red, yellow and white.

Giant winches wrapped with two-inch-thick steel-core mooring lines lurked in the shadows, and bollards popped up randomly like iron mushrooms. The smoke from the huge gas grill added to the general murkiness. The throbbing of the giant propeller just under our feet would have made conversation difficult enough without the karaoke music blaring in the corner. The Captain leaned into my ear and said: 'You won't find this ambience in any restaurant on land.' Indeed.

|

Yesterday's treat was a trip to the bow. If the stern is all about power, the bow is pure peace. Standing out there in the tiny lookout, the whole ship behind you, only the endless ocean in front of you, you hear nothing but the sibilant plash of water parting around the hull and the silky breeze brushing past your ears.

After the inferno of noise and clamor that is the huge mechanical beast behind you, the bow is as close to pure, heavenly silence as you will get. None of us wanted to leave.

Papeete, Tahiti

Sightseeing and then back to sea

|

Papeete: Container ships rarely stay in port for more than a day, so we were grateful the Captain had arranged for us to be met by an English-speaking Chinese Tahitian lady who took us on a two-hour tour along the north coast of the island to see a spectacular waterfall and to visit the monuments to Captain Cook and the H.M.S. Bounty, the Point Venus lighthouse, all in a shady beach-side park. The water was so calm and inviting!

Afterwards, she dropped us at a jeweler's, where Lila was intent on buying a black pearl necklace, so Cristi and I drifted down the street to a sidewalk café where we lunched on delicious Polynesian-style raw fish marinated in coconut milk and an excellent local beer.

Things are expensive in Papeete. This is true of most places where cruise ships dock, but even more so on an island where everything has to be imported. I paid $7.50 for a four-day-old International Herald Tribune!

|

On board at the end of day, I felt a rumble in the belly of the ship; our giant propeller had begun to turn and suddenly the containers on shore were slipping past the porthole. I stepped out on deck to watch our progress out of the harbor. Pilot tugs on either side guided us through the tight turns in the fading light. A rainbow spanned the magnificent headland of Tahiti.

The Point Venus lighthouse flashed like a star on the horizon, and a wooden Polynesian barge with red gaff-rigged sails plowed soundlessly off to starboard.

|

We cleared the harbor entrance just as the sun sank into the ocean; our tugs turned back. We were once again at sea. A surge of joy lifted my heart.

A full day at sea puts everyone into lighter spirits. Ports are hard work and obviously stressful - all that coordination! The shippers must have their containers in port, the trucks and loaders have to be there to move them around, the cranes have to be working, the port agent has to sign off on each cargo, the containers all have to be accounted for - what goes on, what goes off, which containers are empty and which are full - and full of what - and who's paying for each. There's offloading sludge as well as topping up fuel tanks. And, with all those vehicles moving around on the dock, the crane operators swinging their loads back and forth, workers on dock and deck guiding each container into position... it's easy to see how somebody could get squashed.

Right now, the ship is doing its deepest roll since I boarded in Panama. The Captain says conditions will worsen as our voyage takes us closer and closer to the fierce winter storms racing one after another across the Southern Ocean. 'Then you'll really see what the seaman's life is like!'

|

We 'ladies' were curious about the cargo. The three-million dollar motor yacht hidden among the containers on the foredeck is not the most exotic item on board. There is a reefer filled with French champagne insured for a million euros, a Ferrari, perfumes, insulin, lobsters, explosives and a one-off 1952 Bentley with shark-skin seats belonging to some sheikh!

I have been noticing that, with the shifts in the wind, some of the particulate matter from the stack is settling on the deck, little black bits that we scrape up with our shoes and carry around. Because of the ports she lands in, the ship is in compliance with some of the strictest environmental standards in the world, but in port she's not burning bunker.

|

It takes a while not to be alarmed by the smells on board. There are places where you can smell the heavy, oily fumes of fuel; the chemical smell of the anti-corrosive paint used in the constant battle at sea against the ever-recurring rust permeates the superstructure; and just outside my cabin I get occasional puffs of bottled gas wafting up the stairwell from the Galley.

I wonder how they hide all this on passenger ships.

Nadi, Fiji

The largest Hindu Temple outside India

|

In Fiji our objective was the Hindu Temple at Nadi. It's the largest outside India, where it was made to be shipped to Fiji in pieces and reassembled to serve the large population of Indians who were brought here generations ago to work the British sugar cane plantations. We had to approach the sacred ground on bare feet across the graveled parking lot.

The effect overall was fantastic: no surface unelaborated with sacred carvings and vibrant - even gaudy - paintings; the smoky odor of incense rising from numberless altars; a monotonic voice chanting ceaselessly into a public address system; shadowy interiors marked 'For Devotees Only' with worshipers in saris, bowing low, carrying offerings of fruit or brilliant flowers to the altars.

|

The town of Nadi, where we went next to a shabby little massage parlor, is unremarkable, but Raymond Burr's orchid collection in the tropical nature preserve is definitely worth a visit. My shipmates went; I stayed behind at the relatively luxurious First Landing Resort to loll in the pool before we met up to head back 'home' - which is what the ship was becoming to us all.

I had never visited a country that was a military dictatorship before. Our taxi driver described it thus: 'We have military government, good, no corruption.' In Fiji the unloveliness left over from British colonial rule is unavoidable, and poverty is everywhere. But then we hadn't been whisked from a plane to one of the tourist beaches for which Fiji is famous. The Captain summed it up: he said that the first time he docked here, the Port Agent showed up barefoot riding a bicycle. 'I am not having Port Agent barefoot in my ship. No shoes, no coming in my ship. Out!'

Skipping time zones: when I turn the clock back at bedtime and note despairingly that it's not even eight o'clock, at least I have the consolation of spectacular sunrises. One morning I climbed to my perch on the top step to F Deck, facing aft, a little northeasterly.

|

First a faint pink lined the clouds, then a golden light gradually deepened along the horizon, and puffs of cloud over the indigo water turned from mauve, to rose, to bright pink. On the horizon the clouds opened to form a rose-tinged bowl, scalloped like a seashell, and suddenly the sunlight poured into this bowl like molten gold, too brilliant to look at.

Noumea, New Caledonia

There are only French and Not-French here

|

We had been warned that it's very hard to pay for anything in Noumea, New Caledonia, without local currency, but we never imagined it would be impossible to get local currency. I tried two change machines, two ATMs, and two banks with no luck at all.

Fortunately, before we went our separate ways, Lila lent me 2,500 francs, that I hoped was enough to buy some time in an Internet café and pay my taxi fare back to the ship. After the Internet café, I went in search of an English-language newspaper (no luck there either).

|

Noumea is a bright, clean city with a series of beautifully planted places (squares) running through the middle, but here as in Tahiti I had the powerful impression that there are only two classes of people in these colonies still ruled from Paris: the French and the Not-French, which means the Polynesians (and the occasional hapless tourist).

With a credit card I managed to find a delicious salad and local beer at a pretty park-side café before taxiing back to the ship. I was keenly conscious of the limitations of freighter travel - too little time in port to really enjoy the visit.

|

After New Caledonia, our third port, I suddenly felt a sense of having crossed a lot of geography. It was a lot, in fact. Pouring over the charts, the Captain said that, by the time we get to Sydney, we will have crossed approximately 7,800 nautical miles from Panama - more than a third of the way around the globe.

We got a sample of hands-on training when the fire alarm went off at 3:30 in the afternoon. We had been warned of this, but of course I was engrossed in something when that ear-splitting alarm went off, and I had to bustle to get into my shoes, grab the bulky immersion suit and high-tail it up two flights of stairs to the bridge.

|

From there 'the ladies' watched in awe as the Captain communicated by walkie-talkie with all emergency stations while the other officers and crew simulated a fire in the engine room that eventually 'spread' to the cargo hold.

Finally the Captain sounded 'Abandon Ship' and we trooped down to the boat deck where, one by one, the men climbed into the life boat and started the engine, something all of them must be able to do.

Later when I talked to the Chief in the lounge, I remarked that the emergency lighting system was certainly a comforting idea, because in the dark people are much more apt to panic. He said there would be no backup lighting in the engine room - in case of fire there, everything shuts down. 'How do you see?' I asked. 'You have the light of the fire,' he said!

Sydney, Australia

More than a third of the way around the globe already

|

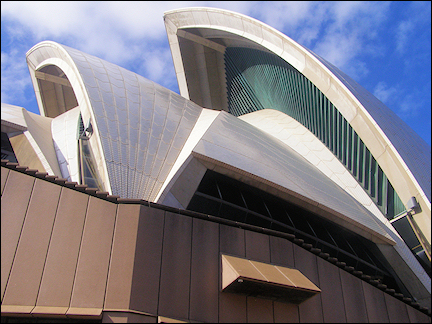

The weather was chilly, the sky brilliantly blue. From the back of the Seamen's Mission van, I could see little in front of us, but when we rounded a stone embankment and the Opera House suddenly rose up on our left like a giant bird flashing silvery wings, I gasped, grabbed my camera, tumbled out onto the pavement and walked toward it in amazement.

No photograph can prepare you for the in-person sight of this architectural poetry. The Captain, Chief and I walked all around it, snapping pictures, and then along Circular Quay and the ferry docks to The Rocks, where the first British prisoners were landed to settle here or die. The day's magic just kept going - here in Australia, on the other side of the world, in the company of two beefy Balkan sailors!

|

Over lunch, I told them how, every time we leave port, I find myself feeling a giddy joy at returning to sea, almost like homecoming, and I asked if they ever felt that. 'No,' the Chief said, 'It's just a job to us now.'

Nineteen miles off the coast, heading south-southwest in a calm sea, there were hundreds of pilot whales around the ship, migrating to the Indian Ocean to breed. They were moving at speed, not playing, although I did see one or two break the surface - their long shiny backs curving gracefully out of the water - and I saw one sound and flap its tail.

Melbourne, Australia

Stuck in the fog

|

As we entered the channel into Melbourne, a fog settled down on us like a giant's thick white feather bed. The port was closed. No ships going out, no ships coming in. We were the only ship in the channel, proceeding at dead-slow speed, pilot on board. We could see nothing on either side. On deck there was no wind and barely a ripple along our hull. It felt as if time itself had stopped.

One of our two new passengers, Ian, is on his fourth freighter voyage but has also traveled by train all across China, Russia, Europe and the Near East, including on the Trans-Siberian Railway. We agreed: it's about the sea, it's about the movement of the train across the rails; it's not especially about the places you pass along the way.

Napier, New Zealand

The place seemed as sanitized as a theme park

|

After passing through Cook Strait, with the snowy peaks of South Island glowing rosily in the sunset, we headed north along the coast of North Island to Napier, New Zealand. The city was leveled in an earthquake in 1931 and completely rebuilt in late-20s Art Deco.

This is its tourist claim to fame, and it makes the most of it, with bricked pedestrian malls, traffic lights that chirp at you, quaint store-fronts, helpful people, and not a poster, dirty-faced child or gum-wrapper visible to the tourist eye. Jaywalking is illegal, but I did it anyway and I was filmed by a crime control unit with four swiveling cameras perched on top. I found this somewhat sinister. It seems the good people of Napier pay their taxes and tolerate no monkey-business. As 'cute' as it was, the place seemed as sanitized as a theme park; it lacked real human charm. I wasn't sorry to get back to the ship.

Tauranga, New Zealand

Only two more weeks to Panama

|

Our last landfall: As we pushed slowly into the narrowing channel of Tauranga, New Zealand, the sun set red in a cloudless sky behind low hills overhanging the ice-blue water. A dark line of conifers profiled the shore. It could have been anywhere on the Atlantic coast of North America. I don't feel any particular need to go ashore. It's cold!

We're losing time here, however. First Mate said we were already a day behind. Other ships are coming in and we have to wait for traffic to clear in the channel. Meanwhile, there's no shore leave, so we stare at the stacks of Radiata pine trunks on the dock, all perfectly round and all perfectly the same length, cultivated in vast inland forests and waiting for export to China and India. Even when they're farmed, dead trees make me a little sad. I'm ready to go. I'm not in a hurry to get anywhere; I just prefer to be at sea.

|

Leaving the land. I see that my time is limited, shrinking instead of expanding, as it was when I faced the disappearing horizon west of the Americas. A sadness pricks my heart at the knowledge that this magical voyage will soon be done. Two weeks to Panama.

I finally got around to asking the Captain how long it would take to stop the ship. He started to answer that it would depend on conditions, the speed, currents, weather, wind, and I interrupted to ask, 'So if there were a man overboard, what would happen?' He grinned puckishly and said, 'If conditions are really bad, we just say a moment of silence and go on.'

The ride is getting bumpier. My shipmates said they had trouble sleeping last night - I rocked like a baby. But this morning there was absolutely no way to stand still enough to do yoga.

We're hitting squall after squall, and every once in a while the bow slaps into a wave with such force that it resounds through the hull and feels as if we've crashed into something solid.

|

Approaching Panama you can smell the tropics. Out on deck in the dark, the stars faintly winking on and off as low clouds stream invisibly across the sky, there's a new, heavy warmth to the air. I feel it on my skin, taste it in my nose; it's humid, soft and kind. This is surely what they mean by 'balmy tropical nights.' It feels like I'm almost home.

The author is a daughter and granddaughter of travelers and sailors. The complete tale of her adventure, Letters from the Pacific , is available in both paperback and as a Kindle Book. She has long made her home in Costa Rica.