Portugal's Jewish heritage

|

Reportage of a quest for the Jewish heritage in Portugal, with visits to current synagogues in Lisbon and Belmonte and to the former synagogues in Castelo de Vide and Tomar, which date from before the Inquisition era. Conversations with historians and rabbis and visits to historic Jewish quarters, Judiaria, like the famous Alfama in Lisbon; meetings with Marranos, who kept their faith secretly for over 500 years.

Travelogue & photos: Piet de Geus

Lisbon

In the former ghetto nowadays the Fado sounds

Between clotheslines with laundry and bird cages we climb up winding stairs from one square to another. Spring sun paints sharp shadows in the narrow, confining streets of Alfama. When we turn the umptieth corner, Ricardo Bottini stops and points out a sign: Rua da Judiaria. Bottino, professor of art history in Lisbon, accompanies me for a week on a quest for Jewish life in his country. When we pass by the Conceição church, he explains that it was built on the foundations of a former synagogue.

|

When we continue our climb after lunch to Castelo São Jorge, my legs tell me that I washed down the broiled sardines with a little too much vinho verde. While we were eating, I realized that nothing remains to be seen of the Jewish origins of this famous working class neighborhood, unless I'd dig up the foundations of the church with my own two hands.

Bottino doesn't seem to notice my disappointment. Leaning on the barrel of a medieval canon, he draws an imaginary line with his hand through the city beneath us and enthousiastically says: "Look, the remains show clearly where the wall was that King Fernão built around the city. And there, between the wall and the Tagus, he founded the Judiaria of Alfama in 1373. The wall was meant to protect only Christians."

While we cross the busy city center of Lisbon, I read in the Jewish Travel Guide 1995 that nowadays Portugal with its 700 Jews has "one of the smallest Jewish communities in Europe." "There are more," Bottino says, while he guides me to a cross street of the Avenida da Liberdade, "At most 2000, but that includes the foreigners who work and live here." Behind a high fence we find the Sha'arei Tikwah synagogue, one of two in the whole country that has Shabbat services.

Rabbi Dov Cohen takes time to walk us through the building which was dedicated in 1902 and tell us about his congregation. "Lisbon has about a hundred Jewish families, among whom many merchants and intellectuals. Most of them are not religious. Except for two or three of them, they're from outside Portugal; most of them fled North Africa, starting in the 1920s. This congregation is orthodox, but even the forty members who regularly visit services I wouldn't call orthodox." It doesn't seem to bother the rabbi: with a cheerful shalom he says goodbye to us.

|

In the evening we return to Alfama for dinner. After the traditional cabbage soup, Bottino is ready to provide us with some numbers: "During the Middle Ages there was no census, but from tax registers we can deduce that there must have been about 30,000 Jews in Portugal."

"That doesn't include Alentejo and Algarve, whose registers were lost. Other historians count 75,000. So, let's stay on the safe side and conclude that 3 to 8 percent of the one million Portuguese..." The lights are dimmed and Bottini immediately stops speaking. A female singer with a black shawl sings a fado song, accompanied by guitar and guitarra. That is a matter of such gravity that even the waiters interrupt their work.

When half an hour later the lights come up again, our main course is served. While Bottini polishes off the fried goat, he draws the story of the eclipse of Judaism in broad strokes: "In 1496 King Manuel decreed that Jews had to be baptized and become Christians or leave the country. The Judiaria in Alfama was ended by a pogrom in 1506 in which 3000 Jews were killed. The Inquisition did the rest between 1506 and 1821 with its stakes." The light is dimmed again. This time a male singer performs. He mourns his Maria morena so heartbreakingly that we would have been quiet even if we didn't have to.

Evora

Synagogue discovered in old warehouse

|

Early next morning we leave Lisbon. An hour after we drove underneath the enormous Christ statue on the south bank of the Tagus, we find ourselves between rolling fields of grain in the Alentejo. Even though it's only spring, we open the car windows.

"This is the hottest part of Portugal," Bottino says, while he unbuttons a button of his shirt. "The heat slows down the pace of life, which is occasion for countless jokes in the rest of the country." He answers my inquisitive look with "okay, one." "Ask an Alentejan carpenter why he sits during his work and he'll answer that he has tried to do it lying down, but found out that that takes more energy."

When we arrive in Evora, the Praça do Giraldo is crowded. Under the arcades on its east side groups of men are chatting. On the square itself tourists with maps walk from cathedral to monastery and from aquaduct to Roman temple. Evora has so many sights that Unesco declared the whole city world heritage in 1986.

We enter a pasteleria under the arcade, to have cake and a bica, the Portuguese version of espresso, while we keep standing, a Portuguese custom. Then Bottino drags me to an alley at the other side of the square. I notice that we are entering the only part that has been left white on the tourist map of the city. "This neighborhood was an important center of Jewish life in the Middle Ages. Spinoza was born here." Bottino tries, but doesn't succeed, to keep a straight face. Apart from the inhabitants of Evora, everyone in the world assigns that honor to Amsterdam, The Netherlands, where his parents had fled to escape Inquisition.

|

While we leasurely stroll in the deserted streets, Bottino points out which of the low white houses are from the 15th century.

"Fortunately the importance of Evora decreased after the 17th century and it became a center of agriculture," he says dead serious, "otherwise, nothing of of this quarter would have remained. The university is doing research here now and a few months ago the old synagogue was discovered in a warehouse. The city council wants to buy and restore it. Then, eventually, this part of town will be on the tourist maps. Lately three synagogues were discovered in a vast area around Evora."

Bottino doesn't sound happy. The professor, who fled the Salazar dictatorship as a conscientious objector, is even visibly annoyed. "There is so much more, but we still have a huge backlog in historical research, in every field. As opponents of Salazar we hoped that the Carnation Revolution would mean an end to the indifference to our history, but in general that hasn't happened. The cities have to finance the research and in the poor Alentejo city councils prefer to extend the electricity grid, or provide telephone service and running water."

"That seems obvious, but much depends on the fields of interest of the mayor and the city council. The mayor of a village in the south of the Alentejo has a background in archeology and his administration has hired three archeologists. There are a few sites now and a small museum. Slowly tourists begin to visit and bring money to the village. Maybe this example will be followed," Bottino says while we walk back to the Praça do Giraldo. There is some optimism in his voice, but also exhaustion. He knows it will take a lot of convincing to make that happen.

Castelo de Vide

In the past this was a dangerous border area

|

By nightfall we arrive in Castelo de Vide, which lies at a distance of 12 kilometers from the Spanish border on a slope of the Serra de S. Marmede. Castelo de Vide is famous for its 300 wells and the mineral water of the same name. Of the over 150 towns in Portugal of which is known that Jews lived there, it has the best conservated Jewish quarter. Here President Mario Soares apologized in 1988 for the persecution of the Jews in Portugal.

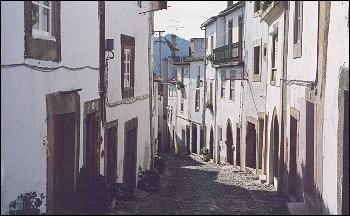

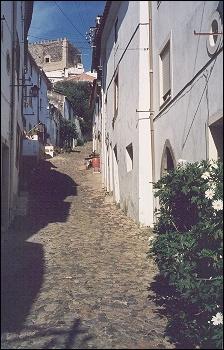

Early in the morning, before the coaches unload their tourists, we go there to take a look. If you understand the system, the signs are superfluous: walk to the castle which towers over the village and the last neigborhood outside the medieval walls is the Jewish quarter, no mistake possible.

The white-stuccoed houses on the maze-like cobblestoned streets and stairs have all been carefully restored and often still have their original solid windows and doors. Between the houses are gardens with roses and shrubs. Between the cobblestones on the streets grow daisies here and there and in front of many houses sit vazes or olive oil cans with flowers and plants. Almost every cross street reveals a gorgeous view: upward of the castle and downward of the roofs of the lower lying parts of the village. There are no youngsters here, only old people. The women all wear a headscarf to protect themselves from the sun and often they wear a hat on top of that.

|

At the center of the neighborhood is a 13th century synagogue, the oldest in the country. In front of this low, rectangular building, I read the brochure that the regional Tourist Office provides.

"Medieval wealth attracted an important Jewish community," I read out loud. "Nonsense," says Bottino, laughing, while we step aside to let a man on a donkey pass by. "In medieval times everyone wanted to live on the coast and this dangerous border area was the least popular. The kings had to entice people to live here by offering tax exemptions; they wanted people to live here as a kind of buffer against Spain. That is why the Jews here were initially left alone, when elsewhere they were already persecuted. Many of them had fled Spain and of course were highly motivated to defend the border."

Belmonte

The "Marranos" secretly adhered to their religion

Belmonte lies in the foothills of the Serra de Estrella, Portugal's highest mountain ridge. In this remote region lives a group of a few hundred so-called Marranos, who for hundreds of years kept their Jewish faith. On the outside they acted like good catholics, but in secret they kept and passed on their tradition. They hid their Shabbat lights in a closet. When one of them died, they waited a little before they called the priest, to be able to wash the body according to Jewish tradition.

In 1991 the Marranos of Belmonte were "outed" when anthropologist Frederic Brenner sold his documentary about their secret lives to television networks. In his study in the city hall, mayor Antonio Pinto, a medical doctor by profession, tells us how this put his sleepy rural community on the map of Portugal.

"Belmonte was only known for being the birthplace of Cabral, who discovered Brazil in 1500, but nowadays everyone speaks about Belmonte and the Jews. We get tourists from America, Israel and also from Portugal, because people are becoming aware that there are Jews in their country. I always knew, of course, like everyone in Belmonte. There are 350 Jews here, which is a large group in a population of 3000."

The mayor makes himself comfortable before he tells us the news: "Three months ago the Israeli embassador visited me. Together we chose a town in Israel and soon Belmonte will be the sister city of Rosh Pina."

|

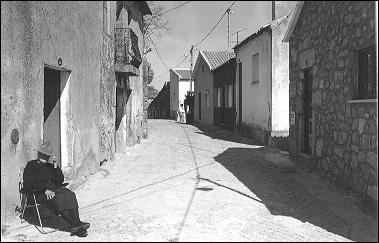

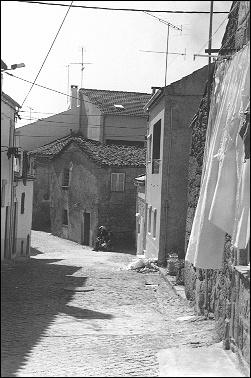

The walk in the village a little later soon becomes a search. In the cemetary, a sea of plastic flowers and marble in the shadow of the castle ruin, we find between the numerous crosses only one Star of David.

On the other side of the remains of the castle we descend via dusty streets. There are no tourists, the neighborhood looks abandoned in the spring sun. Here and there a dog barks with audible aversion; a few old people are dozing in the shade. Nothing betrays the Jewish character of the grey neighborhood, there's not even one single mezuzah next to a door.

On the other side of Belmonte Shlomo Azulai sits in the sun on the balcony of his apartment in a new building. With a yarmulke on his bearded head, the young rabbi is "lerning" (studying Jewish texts) in his shirtsleeves. In 1994 Azulai, immediately after he finished his rabbinical studies, was sent to Belmonte by the Jewish Agency, a zionist organisation which takes care of Jews outside Israel. When he sees us coming, he puts on his jacket and opens the door. Before we can enter, we have to put on yarmulkes, because part of his apartment is used as a synagogue.

Azulai leads us to a room which fits 30 men, with a podium for reading Torah. "No, even though that is part of my job, no Marrano has moved to Israel yet. It is hard to take people who have seven or eight hundred years old roots here out of their community. I am the second rabbi in the four years that the synagogue exists. In the past everything took place in the home, and all Marrano rituals were performed by women."

Azulai follows my gaze at the horizontal crack in the wall, behind which is the room where women have to follow the service. "They don't mind that they have to sit separately now. Let's not forget that the Marranos lived separated from the Jewish people for 500 years. Because of the orally transmitted tradition they hardly lived according to orthodox standards. On top of that many catholic elements found their way into their religious rituals. The sephardic chief rabbi Mordechai Ediaho decided in 1990, after research into their background, that they are Jews, but the men had to be circumcised and everyone had to immerse themselves in the mikvah, the ritual bath. In particular the older people didn't want that and preferred to die with their own tradition. Twenty families joined the orthodox congregation."

|

When we return the yarmulkes and say goodbye, Azulai says it will be hard to speak with Marranos. "Because of all the outside attention they have become shy," he explains. Apparently he is so convinced of his mission that he forgets that he is an outsider, too.

On the other side of the street we happen to run into Abílio Morão Henriques and Amélia Henriques Morão, a middle-aged Marrano couple who own a textile plant here. They are more than willing to speak with us and immediately invite us in. A van which arrives to pick up clothes has to wait. "I follow the service in the synagogue, without understanding anything. I don't know any Hebrew. But at home we still do things the way we used to," Amélia says shyly.

Abílio was a member of the board of the orthodox congregation. "I left because the rabbi is so pushy. The last one wasn't, he was a wise man. He also was a lot older," he says with some regret in his voice. "On Shabbat I still go to the synagogue, but nowadays there's a lot of strife in the Marrano community of Belmonte. Some try to be as orthodox as the rabbi. The ones who don't, are shunned. The orthodox also separate themselves from the Gentiles."

In the five years since it became known and outside interference started, the Marrano community already seems to be falling apart. I wonder how long it will take for this last remaining Jewish community, which withstood 5 centuries of oppression, to just become part of Portuguese history. Before we are allowed to leave, Amélia sings a song, between the long rows of racks with pants, which has been passed on with love from generation to generation for all these centuries.

Tomar

Mainly know for its Templars

On the way back to Lisbon we stop in Tomar, which owes its fame to a gigantic Templar monastry fortress. At the foot of the fortress, in another one of those modest medieval streets, we find the synagogue. With the ones in Castelo de Vide and Guarda this is the third synagogue in Portugal which dates from before the Inquisition, not counting the ones that were recently discovered and which double this number. Luis Vasco, a Marrano who doesn't wear a yarmulke but a black fisherman's cap, is the custodian.

"This synagogue was built in the 15th century," he says, pointing at the oriental ornaments that decorate the four columns which support the vaults. "After the decree of 1496 it had to be abandoned again. After that, it was a prison, a warehouse and a hay shed. Since 1939 it has been a Jewish museum."

|

In 1992 this synagogue was the backdrop of a celebration Vasco won't forget for the rest of his life: "After five centuries we had our first Yom Kippur. An English-Portuguese fishmonger gave us the Holy Ark, from Tanger came a rabbi and there were Jews from South Africa, France, Holland, Israel and Lisbon - all in all fifty people. It was a national event, there were television crews, newspaper reporters, you name it."

Basking in the memory, he leafs through a stack of magazines which he keeps next to the entrance and points out pictures in which he is visible. A large headline says: "Jews celebrate Yom Kippur in Portugal." Fifty Jews who celebrate the Day of Atonement - five centuries after the Inquisition began that is big news in Portugal.